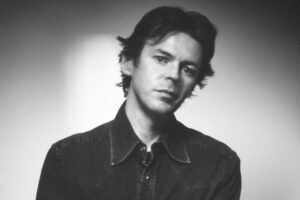

Her career as a model, agent and activist pushed Black women into the spotlight

One of the most consequential models of the 20th century can’t remember a specific moment when she felt beautiful.

“When you’re a warrior, you ain’t got time to be worrying about things like that,” said Bethann Hardison, 80. “A warrior isn’t beautiful.”

Hardison spoke with me via Zoom recently about Invisible Beauty, the new documentary that she made with Frédéric Tcheng about her life and work as a model, agent, and most of all, advocate for racial diversity in modeling, creating a path for people such as Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks, Beverly Johnson, and Iman.

She’s donned all kinds of sartorial artworks and made them sing. But as for feeling beautiful, or remembering her outfits? There were few moments of note, save, perhaps, for her first and second weddings.

“I’m not insecure about what I look like,” Hardison said. She just never experienced seeing herself in the mirror and feeling a gush of self-satisfaction.

“Oh, no, I’ve never had that,” Hardison said. “No, my feet are too … I don’t normally wear makeup. I’m not even caught up on things like that. I’d never thought I wasn’t attractive because I had so many men coming after me. I knew that. God, I always had boys, young, old — didn’t matter. I’ve always had … I know I’m attractive. I knew that.”

Hardison was one of a group of Black models who revolutionized what runway modeling could be: theatrical, soulful, an art that freed the model to engage in a more individualized and physical interpretation and appreciation of the couture she was showcasing. The 1973 Paris shows known as “The Battle of Versailles,” the first time American designers competed directly with European designers, was a rocket launcher for Hardison’s career. But years later, she witnessed an aesthetic backlash against those same models. Tscheng documents the rise of a white, Eastern European homogeneity — one that seemed to revel in malnourishment — that became the preferred look for designers and the people casting runway shows and magazine editorials.

Hardison responded with years of confrontation and record-keeping, making it plain that Black models had been erased from these beauty-defining arenas by publishing numerical statistics of who was walking in runway shows. She started her own agency, helping to make people like Tyson Beckford and Liya Kebede into stars. The next mountain was pushing for more than just token representation, i.e., one or two Black models in a show that employed three dozen. (A similar dynamic continues now with the casting of curve or plus size models, where a show with one plus model is considered “size inclusive.”)

Hardison is uninterested in engaging with the casting of models as a labor and discrimination issue to be reformed through organizing. Perhaps what will remain puzzling to some after screening Invisible Beauty is Hardison’s faith that the people who hold power in fashion want to do better. The most radical fashion insider of her generation remains steadfast, continuing to build out the runway for designers like Brother Vellies founder Aurora James to demand representation not just on the runway, but on company boards and in C-suites. Hardison has fashioned an army of devotees, who are following in her stead to ensure that Black models and designers aren’t merely a trend, but a permanent fixture.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You noticed a problem and took action to remedy it. Was it just so you could continue to work? Or did it always feel like something you were being called to fix for others as well?

Both. Yes, you’re called to do it. Someone wants to do it, wants you to do it, and they call you, and they actually tell you to come home to do it. It is like a job. It is like your duty … and your responsibility, because you’re that person that’s cut out for that. I can talk to the industry because I know the industry. So that makes it a little bit more like I believe in the industry. I have enough faith that they can hear what I’m saying.

Why do you have such faith in designers doing the right thing, especially when it seems like they won’t unless someone is there reminding them?

Because I grew up in a business that I understand, the mind of the designer. And I also watched the business change by them no longer deciding things within their own offices and their own design studios. They had outside help. They started hiring stylists, they started hiring casting directors. You see the business change. … The game is changing. You’re no longer going to sit there and just go off and talk, go ahead and have a straight meeting with Calvin [Klein]. It’s going to be someone else who’s going to decide these things. I just know that no matter who they are characteristically or where they were born, if they’re a fashion designer — this is something that I know in my mind — the last thing they think they are is racist. And you just play that card.

You’re able to appeal to the better angels of their nature?

I just think that they’re more ignorant, I do, than I think they’re racist. I can live with ignorance because I can shift it. Racism won’t shift. If I knew that I was talking to someone who said, ‘Don’t talk to me about those Black people,’ I would leave that person alone and go talk to the other guy. I could leave somebody in their conviction. I’m not mad at them if they don’t like me or don’t like what I look like. I can stand that, because he’s clear. But those who are not clear, functioning like that’s what they are, I got to go help them.

You grew up in Brooklyn. But what did you learn from the time you spent with relatives in North Carolina?

A lot of things. I loved that I had the opportunity of being a city kid and having that opportunity to experience that. Because I lived in rural North Carolina. … I lived where there was outhouses and the slop bucket for night, priming the well to get your water out of the well, going out there and having to go get the chicken when I was 10 years old and convince him that I wasn’t going to kill him, and yet have to kill him, wring his neck. It keeps you balanced in some way between the North and the South. And the experience of having to go upstairs to watch a movie — the Blacks had to be upstairs, the whites had to be downstairs. When you tell that to some white people, they think it’s so awful. And I keep saying, “It wasn’t awful.” It was nothing awful about any of my experiences in North Carolina. Not when it comes down to other whites and Blacks. Being eaten up alive when I went into the backwoods with my uncle, and yellowjackets: that was something you won’t forget.

You talk about witnessing this period where Black models make this incredible impact at Versailles. And then this progress just disappears. What keeps you going when you have so intimately experienced the disappointment of being a part of progress and then seeing just how easily it can go away?

Basically, you just gotta put your big girl pants on and just get back into the race. Because we started seeing it, we were seeing progress right away. As soon as they say, “No blacks, no ethnics,” and you get them to stop saying that.

The model agencies start to get better and they start taking on better girls. Because the casting people are not wrong; if you don’t have good girls — I don’t care if they’re Black, white, Asian, whatever — you’re not going to book. The model agencies got stuck with a few girls because they felt like they didn’t want to have more than they could really manage, more they could sell.

I can see outside of the casting director, even though they’re saying things that are so blatant, but that’s the way we speak in our industry. We have to talk about physicality and all. But at the end of the day, it winded up being something they stopped saying. It helped the modeling agencies start to find other girls and it really was better. And then, all of a sudden, as it got better, it started slipping back a little bit. So you just gotta get back in the game. That’s the only thing you can do if you really want to see permanent change.

In the context of what we’ve been seeing over the past year in the labor movement, with the WGA, SAG-AFTRA, UPS, the UAW, do you think it makes sense for models to organize?

No, I’ve never been a proponent of models needing to have a union. But that’s because I’m old-school, I guess. And I was a former model and a former model agent, manager and agency owner, so I don’t tend to go down that road. I just believe that models should be educated well by their people that represent them. And that’s what I always try to do. Because I didn’t want to have a model agency, so I was definitely — I was rogue from the moment I started.

I really believed in the talent more so than I did in the industry. And I was there to help change the industry in the way I could, best I could, by the way I just functioned. … And we don’t have what we had in the ’80s, in the ’90s, it’s not as dangerous as it was before for the girls coming in. There’s more awareness. The CFDA [Council of Fashion Designers of America] even tried to make sure there was a concern for the health of models behind the stage. They’ve started making regulations and saying it every time there is a season. The girls are more aware now as well. Model agencies are not the way it used to be where you have the guys from Europe just investing and wanting to get the girls and all that. A lot of that’s gone. That business is different. I don’t think that it’s necessary. … I think that right now, the industry has improved. They’ve passed through that tunnel.

When you look at the contemporary landscape of African American designers, whether it’s Aurora James or LaQuan Smith or Christopher John Rogers or Sergio Hudson, or others, what’s your hope for the future?

I just want them all to have successful businesses that they can leave to their children. If they’re so committed to being designers and starting these businesses, that if they could just be good business people. Because it is very interesting to be a creative person. But at the end of the day, I want them all to be where they can grow old and they still have a business.

Why is that so hard?

Well, it’s just hard because I think it swerves in and out, the industry itself, the retail, the wholesale. It’s not as easy for even the retailer to stay in business. People don’t shop the way they used to, when they start doing things online. I think it changed the game for everybody. Everybody has to play and hold their cards close to the chest.

Source : Andscape